Part 4: On Dreams

Whose dream is it, anyway? Or, dreaming our way out of a Big Dumb Gold Rush...

I want to start the final installment of this series by thanking my readers and subscribers who are not tech-heads for your patience during All-AI Autumn here on the newsletter. While I hope that you have found some interesting information and food for thought in here, I know that some of y’all are here for something else entirely. So, I see you, I appreciate your support and I’ll be back on a broader variety of topics (and a regular twice-monthly schedule) real soon. <3

For the rest of you futures freaks, welcome back to the final installment of The Big Dumb Gold Rush, my series on AI developments—particularly as they relate to the worst aspects of U.S. culture at large. I’ve picked up some new subscribers since the last installment (hi! welcome!), so while I hope you’ll read the rest of the series, there’s no prerequisites to understand this final chapter.

After writing about the function of AI, its value/s, and the power dynamics influencing the tech sector more broadly, it’s time to talk about dreams. Dreams as in:

visions of the future,

collective and individual aspirations,

& expressions of the subconscious.

What is the techno-optimist’s dream AI scenario? What do our fears about AI reflect about our present conditions? Whose sweet dream/beautiful nightmare are we most likely to be living within soon?

Since I live in the U.S. and I started this essay on Election Day, it might be worthwhile to begin by thinking about the dreams of our presidential candidates—what we can gather about their desires for the future when it comes to AI and the tech sector. The most recent installment, On Power, covered ties between tech and far-right neo-monarchists/authoritarians in far more detail. Now that a bonafide Peter Thiel acolyte/Silicon Valley creepazoid (Vance) will be a heartbeat away from the big, bad button of it all, it seems particularly crucial to keep an eye on all that.

I’m also curious (read: terrified) to see how the fusion of the Christian fundamentalist set and the new Tech Right goes. They don’t dream the same dream at all…do they? I predict a robust coalition built on the entrenchment of power as conceived of in The West (patriarchy, white supremacy, “rationality,” hyper-individualism), the outsourcing of complex work in the present to Savior figures (who will show up any minute now), and the public, enthusiastic punishment of heretics. For more on the cult-y dynamic of Silicon Valley in the age of AI, read this when you’re done.

It’s nearly impossible to predict what Trump is or isn’t going to do, because he’s a famously capricious and probably senile grifter who goes with the flow of whomever most recently fluffed him. And in this election cycle, some of his most ardent support came from tech barons like Elon Musk. Brian Merchant summed up this fusion better than I could in his piece here, but I want to share this quote which I hope illuminates the way in which—despite their “culturally liberal” trappings—the tech industry in the social media and data mining era was never going to be a friend to the non-billionaire.

“Our public and shared spaces, online and off, have been thoroughly privatized and commodified…Disaffection, alienation, and isolation are rampant, and all are byproducts of the hyper-capitalized digital world that Silicon Valley has constructed for us to inhabit…It is a brittle, hollow world that fosters animosity and resentment, where we have long known rage is promoted above empathy, where transforming the human experience into a march through a casino is the goal. A world obsessed with score-settling, with outsourcing, with gambling. It’s no wonder, ultimately, that Trump embraced Silicon Valley, and it embraced Trump.”

As for Harris, I see no real need to add my voice to the clamor of the “what went wrong” victory/despair lap. What I will say is that I think that the logic of the social media era (and the pattern of its slow crumbling) has a lot in common with the neoliberal order as represented by the Democratic party. Bland gestures toward “the future” already felt brittle during the 2020 campaign and they were ready to splinter this time. A performance of the aesthetics of acceptable political opinion is not enough for people suffering under difficult material realities and the collective moral injury of funding a live-streamed genocide.

In the post-election progressive’s earnest usage of social media, I see a cousin to the flailing of a directionless party. Yesterday, I re-installed the app and logged in to my Dead Instagram for a minute to try to set up a DM auto-responder. On the feed, I saw infographics about who to be mad at and why, inspirational quotes from radicals taken out of context, and arguments about whether white women should adopt another secret code to mark us as “one of the good ones.” We can wear a bracelet, re-post a quote, or share the right article to perform righteousness. We didn’t vote for the bad man, so we can reclaim our righteous victimhood, in words alone, and call it action. Who does it benefit when personal expression through a digital avatar is perceived as a legitimate site of liberation?

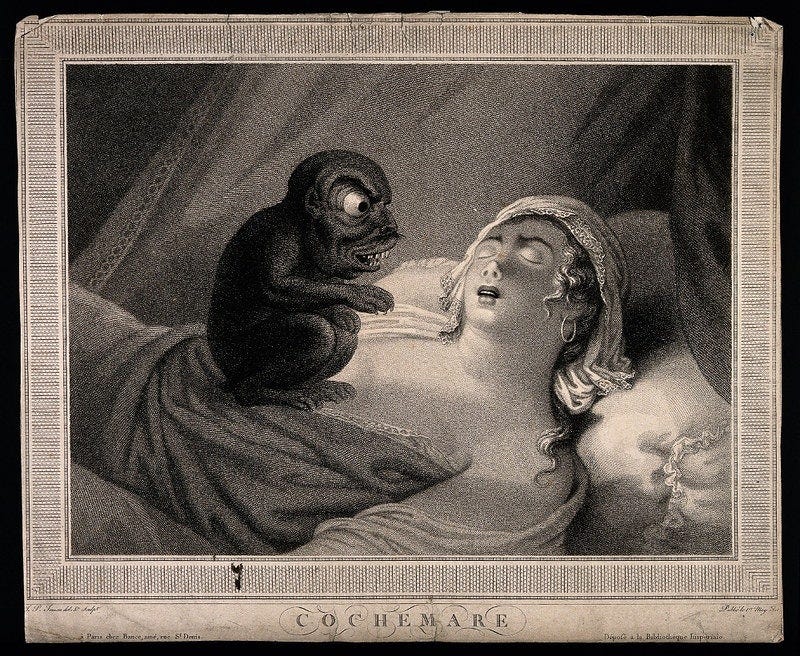

Meanwhile, in Reels, an algorithm that’s forgotten me in my absence served up wall to wall AI body horror. [note: I don’t mean that bodies and faces like these (fat, deviant from health/beauty standards, etc.) are horrific, but that the augmentation of reality pushed in that direction was a horror to behold.] “There’s nothing wrong with cellulite” plastered over a scantily clad woman with a truly impossible waist to thigh ratio, AI generated thighs jiggling pleasantly. Disfigured human faces that blurred the edge of the possible one after the other, seemingly begging for digital alms. Same thighs, but mounting a bicycle. The Christmas tree being hauled in to Rockefeller Center. Another distorted face, but this time in full makeup. Truly mind boggling breasts straining at a bikini while being violently cracked at the chiropractor. The faces in particular made it into my dreams last night.

I need to think and read more about what it means to organize and live a digital/embodied hybrid of a life in this age of rapid deterioration and absurdism, but expect to write more about particular lessons for those of us searching for something real-er soon.

Back to the day after: It’s hard to know what to expect in this realm from another Trump term, but I expect (until their egos collide and they inevitably fall out) Musk will be heavily involved in dreaming the near-term policy future for AI. So far, we know that Trump wants to repeal the Biden era executive order on AI—or at least parts of it that specifically address problems baked into current tech issues like algorithmic bias, and increased fossil fuel consumption needed to power the increase of data centers. Trump’s team claims that order as written has a “radical left wing agenda” (can you find it? I think it might be in parts d and f.) I fucking wish. I think any flavor of “left wing agenda” could have helped us avoid all this for another four years, but I’ll shut up about that for now. Good thing there aren’t any terrible feedback loops already baked in to our large language models that contribute to the worst of this right wing coalition’s impulses!

Outside the distorted hell-realm of U.S. electoral politics, what else has been dreamed up lately?

First, I’m curious to hear from anyone who’s experimented in depth with the new custom AI podcasts in Google Notebook. They might be, as far as I’ve seen, the furthest frontier of the “for you” filter bubble. Choose a topic—a favorite TV show, a forgotten sapphic poet, a Civil War general—and generated voices read a generated script. (This article shares examples from their own experiment on Kafka’s Metamorphosis.) In the newest update, you can specify an audience and receive a custom analysis and tone. Irreverent post-GirlBoss white millenials (Not enough to save Kamala), “Just Asking Questions” ‘roided out masculinity grifters (Not enough podcasts by them yet), tenderqueer anime stans, and so on. I imagine we aren’t far from a direct injection of our personal data-generated consumer preferences profile into an engine like this, and the advent of a truly customized media landscape.

If establishment media hadn’t already crumbled, been paywalled off, and shrugged off by a huge proportion of the population, I might feel better about this one. If I could trust that the scripts weren’t being generated off of the kind of sketchy models that have unearthed such bias and plain wrong information in their early days of use, not to mention being trained on their own cannibalized AI slop, yeah, maybe. I can see the appeal of a consistent, comforting voice telling you things you need to know in a way you can relate to and understand. But media is a world in which we need a combination of gatekeepers and robust community networks of real-life engagement. Many, many Americans live with neither. and it makes us less informed, disempowered in daily life, and extremely lonely.

The loneliness is also at the heart of one of the more dystopian social AI products I’ve seen throughout this exploration.

The hubbub about The Friend took off a while now at the products release, when it received all the eye-rolling and ridicule I might also instinctively lob its way. In case the trailer was unclear or you skipped it, the Friend is an always-listening pendant microphone connected to an in-app LLM (large language model). It listens to your daily life, including interactions with IRL friends, and sends periodic texts through the app that respond to the day’s events. You can also directly text your Friend or seek communication by pushing the pendant’s button. As many people pointed out immediately, the trailer reads like a Black Mirror episode. Given that social AI chatbots are already extremely available and somewhat widely used, I won’t pretend that non-judgmental listening isn’t something many people crave.

Even one of founder Avi Schiffmann’s stated dreams for the Friend isn’t, on its face, all that sinister. In a long interview with Fortune, he speculated (based in part on his own experience testing the product) that users could improve their emotional intelligence by having a judgment-free, all-seeing relationship with a neutral-ish party (the Friend is programmed to be mostly supportive and positive), eventually “graduating from the product.” And, you know, maybe making an attempt to improve emotional intelligence rather than making fun of people who never quite made it through those lessons is a net good. If even one incel leaves the forum that’s trying to blackpill him because he bought a Friend, great news for society.

However. I fear the techno-optimist’s tendency to move fast and “solve” things. In response to criticism in that same long interview (and in others), he yadda-yaddas past criticism.

It’s socially dystopian. Well, people said that about dating apps and just look at how we’ve all accepted them now! (Leaving aside, of course, the abject misery many experience using these borderline-mandatory apps.)

LLMs are still emergent technology. “Somehow [they work]. I honestly have no idea [how].” Surely it’s a problem that this founder has “no idea” how the underlying tech works?

What about issues that have cropped up with search, like AI hallucination? “Researchers are paid like five million a year to figure it out. They’ll figure it out.” Ok, cool, good enough for me! Full steam ahead!

What about privacy? Since we don’t store audio or transcripts, it’s not technically illegal to record all the time!

What do you store? Oh, just a comprehensive profile on Friend’s memories and impressions of you and your life.

This net knowledge the Friend builds of its user is interesting. Schiffmann (because he understands how to grab a headline) has controversially compared the relationship to that which an individual has with God. What else could you call “an omnipresent entity that talks to you with no judgment, that’s always with you,” but God? Schiffmann is not religious, but speculates that declining religious participation and belief has something to do with our widespread loneliness. An interesting thesis. I’m not religious either, but isn’t part of the draw of religious practice the engagement with the mystery of it all? When you kneel down to pray, God (usually) doesn’t get back to you with clarity fifteen seconds later. Call me square, but I think there’s something to prayer being, in part, a quiet conversation with oneself. The things we pray about and for might continue to percolate in our conversations, our thoughts, and our dreams. Quite a power to outsource.

Schiffmann also defends the Friend as an addition to a real life social circle rather than a replacement. What if a neutral (again, ish) third-party witness could help you deconstruct what went wrong after a breakup? What if someone less involved could hear that argument you got into with a colleague? To me, this approach to social life hearkens back to my overall (skeptical) feelings about optimization. It’s sort of a Groundhog Day situation. I don’t want to be Andie MacDowell in that scenario, with someone rehashing personal interactions in hopes of gaming or optimizing a relationship. Is it that different from being talked about in therapy? Probably not, but I’m still sour on it. I love literature and film. And so much of what makes stories (and life) compelling is the fact that we can never really know another, nor can we really see ourselves as others do. I don’t want a robot to help me try.

Finally, on the bleary-eyed techno-optimism of it all, I present my favorite portion of that long video interview. Moments after comparing the AI field to “a modern day Los Alamos, in a sense,” Schiffmann urges us not to compare him to Facebook—and not to apply that product’s latter-day sins to the promise of its initial rollout. “All technology is inherently neutral, initially.” Then, seeming to forget the Los Alamos comparison, he adds, “except maybe nuclear weapons.”

And finally-finally, to close out this entire series, I think we should take a selective look at Marc Andreessen’s notorious techno-optimist manifesto. It’s been referenced throughout the series, but given a) that his total contribution to pro-Trump PACs and Republican candidates reportedly topped three million dollars, and b) that Andreessen sort of represents the essence of today’s Silicon Valley superego, let’s check out some highlights of his dream for the AI and beyond tech future. Most of the manifesto is written in “we believe…” statements, to which I respond with my mom’s favorite line: We? You got a mouse in your pocket, Marc?

You can read the entire manifesto here and a number of more thorough and informed responses in many locations. Essentially, in full, the text reads as a ringing endorsement of “the techno-capital machine”, the fusion of existing capitalist markets with emerging technology and the unfettered leadership of the market leaders of the tech sector at all levels of power.

“We believe the ultimate moral defense of markets is that they divert people who otherwise would raise armies and start religions into peacefully productive pursuits.”

IS THAT WHAT’S HAPPENING, MARC? Good thing none of our most recognizable market players have megalomaniacal tendencies, endorsements of state and vigilante violence, or quasi-religious beliefs and practices around their own grandiosity.

“We believe central planning is a doom loop; markets are an upward spiral.”

I know he’s talking about Soviet-style central planning, but earnest question: Isn’t building a near-monopoly field of AGI engines to optimize finance, resource extraction, and other market functions kind of the ultimate in central planning? Is the difference just in the quality of the hypothetical “perfect knowledge” of the new central planners?

“We believe the techno-capital machine is not anti-human – in fact, it may be the most pro-human thing there is. It serves us. The techno-capital machine works for us. All the machines work for us.”

I have a feeling “us” isn’t you and me, dear reader. Are you feeling served? Or served up on a platter for data extraction? Not to mention all those made invisible who work in mines, prisons, and miserable factories to make machines they’ll likely never use. Are they part of the machines, working for us? Or are they…us…too? Are the machines working for them in, like, a long-term, effective altruist, sorta way? Asking for a friend in a cobalt mine.

“We believe Andy Warhol was right when he said, ‘What’s great about this country is America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you can know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.’ Same for the browser, the smartphone, the chatbot.”

Is a smartphone really anything like a Coke? Is it a social good that an Amazon worker pissing in a bottle on the clock can buy the same nifty phone as Bezos? A browser can shape your entire information ecosystem. Is that really on par with the uplifting spiritual power of a Coke? Maybe there’s some clarity hiding here if we talk about the Coca Cola corporation, rather than its iconic ingestible. A Coke drains water resources away from other, more pressing needs. A Coke sees no issue doing business with apartheid regimes. A Coke leads its industry in its own particular type of pollution. But to the user, a Coke is just a refreshing taste of capitalist iconography. Ari Schiffmann might call a Coke “inherently neutral.”

“We believe that we are, have been, and will always be the masters of technology, not mastered by technology. Victim mentality is a curse in every domain of life, including in our relationship with technology – both unnecessary and self-defeating. We are not victims, we are conquerors…”

“We are not victims, we are conquerors!” —52% of white women, again

“…We believe in nature, but we also believe in overcoming nature. We are not primitives, cowering in fear of the lightning bolt. We are the apex predator; the lightning works for us.”

Saying you “believe in” nature is kind of wild. What does that mean? Maybe it makes me primitive, but I kind of think “WE” are nature. I am deeply disinterested in any paradigm that seeks to place humans outside the bounds of nature, in dominion over the Earth, and so on. And you know what? I do cower in fear of the lightning bolt. These new thunderstorms where I live are no joke and that shit is scary. (Counterpoint: the lightning does also work for me because I do a lot of electricity at my job.) Finally, I agree that the “we” Marc references is the apex predator on the planet, but it’s not the flex he thinks it is.

“…no upper bound…”

Infinite growth is a repeated theme of this manifesto. It’s also the core dream of the capitalist system. But it’s a dream, as in, not possible. We are generations deep in arguments that—soon— tech will solve the problems of allowing growth to outpace natural replenishment. From carbon capture to free energy, it’s always just over the horizon—and we’re expected to bet the planet on it. The Earth is a closed and complex system. And even if these losers colonize space too, I just don’t see a way around the limitations of known physical reality. What’s wrong with calling it a day and creating a world where we all have enough? Can’t we just chill on a floating garden in space?

“We believe technology is liberatory. Liberatory of human potential. Liberatory of the human soul, the human spirit. Expanding what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive.

We believe technology opens the space of what it can mean to be human.”

I actually agree. Despite all my cranky de-growth antics, I too find human ingenuity inspirational. I partake in technology. I enjoy typing my thoughts onto a backlit screen, free from eyes strained by lamplight and ink-stained hands. The bicycle? Thrilling. Liberatory as fuck. I record music for a living and it seems like pretty much everyone is stoked that we can turn sound into electricity and then back into sound again! It’s pretty cool. I think that humans are here to fuck around and tinker and build stuff and accidentally form society and culture and ask questions about the universe. I don’t think that feudal tech regimes under a ruthless global economic system based on extraction and minority accumulation have any coherent relationship to the concept of liberation.

“What world are we building for our children and their children, and their children?

A world of fear, guilt, and resentment?

Or a world of ambition, abundance, and adventure?”

This question wraps me all the way back around to the political dreams of my own country, my own self. People on the greater “left” (to the extent that’s even a practical term to use) absolutely need to embrace this question of world-building in specific, material terms. Not some vague, normalization slogan like “build back better” masking the continuation of an oppressive status quo, but a genuine vision.

Fear, guilt and resentment (and our reactive focus on the fears and resentments of our enemies) don’t win. And, if you can’t tell by reading this series, I am fearful and filled with resentments. While I make an effort not to internalize it or individualize it, I also feel the ambient guilt that comes with American citizenship, with whiteness. But those emotions are real, they’re not useful when looking forward.

I think that a lot of people who gobble down Andreessen’s techno-optimism and end up making common cause with unhinged monarchists and depraved billionaires aren’t reacting to the big picture and all its implications so much as they are to the hopeful and challenging tone of this language. Addressing the massive problems set before us—climate change, ascendant global authoritarianism, the long term impacts of colonialism—will take ambition. Not from a couple of billionaires, but from normal people all around the world. As far as abundance, I propose starting with the billionaires to see how far we can stretch what “we” already have. And adventure—for me, it always starts offline.

Thank you so much for reading this series. It was a labor of love and hate, and more than I could have bargained for. I hope you learned something, went down a wormhole of inquiry, or stirred up your own questions about our collective dreams.

This post lays out very interesting possible scenarios for “post-work” living through technological advancement, but I never found a good place to reference or link it.

This guide has useful first steps to protect your writing, data, etc. from being used to train LLMs and other AI systems.

Also—today is my one year Substack anniversary! There are a lot of new people using this platform since then. I hope some of them will find their way here, maybe through you, loyal reader. <3

Until next time, let’s try to dream ourselves elsewhere while keeping our feet on solid ground.

—TRW

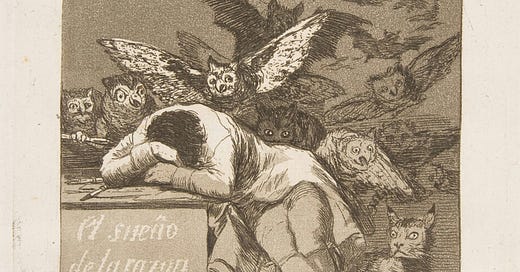

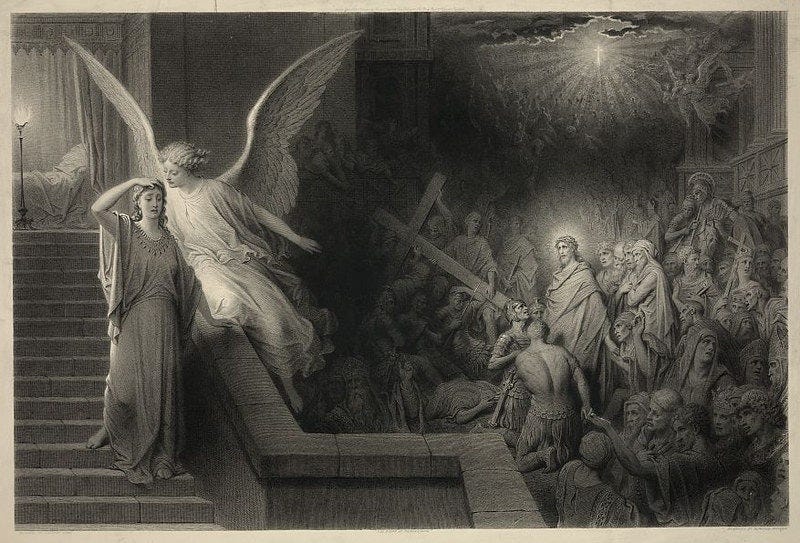

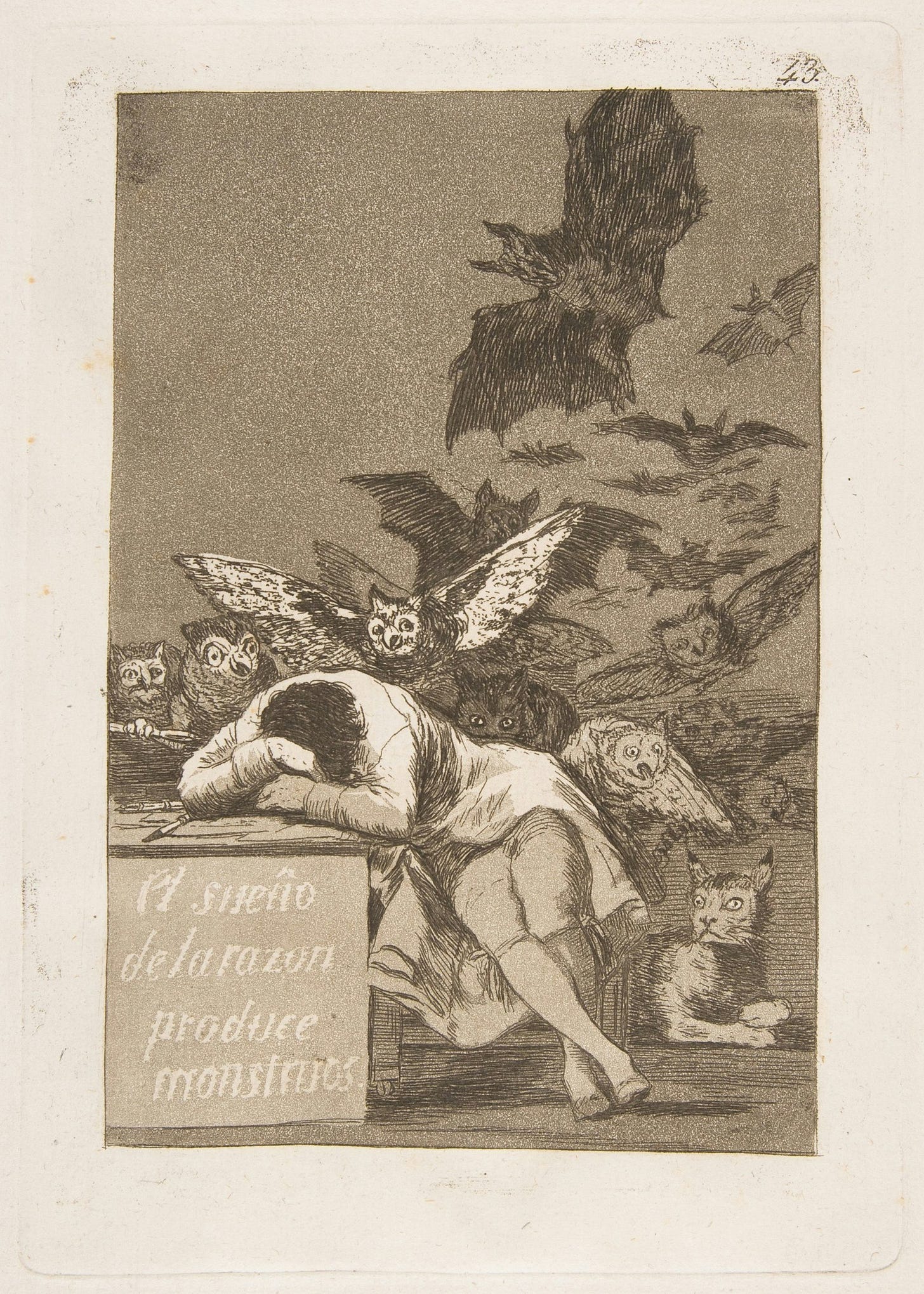

Happy stackiversary! How apropos, the sleep of reason produces the dreams of monsters. Like those AI people thinking Her and Elysium were utopian visions. Musk telling people to brace for economic hard times but trust their savior will turn it around. The "any minute now"s will start in January I'll bet. I'm crawling on the carpet like a crackhead looking for illusory silver linings, but I think, at least, there's an unstoppable momentum toward a total skepticism of big tech, they're speedrunning that shit, and will reap what they sow sooner than later.