Welcome back to the Big Dumb Gold Rush, where this week we’ll focus on AI’s function. What can/’t it do; what should/’nt it do; how is it already being used and what are the impacts on our functioning as humans? If you didn’t read the introduction, I already shared the important caveat that, yes, there are probably many things with which “AI,” and particularly large language models can help us. But what is most visible during the current boom (and maybe bubble?) is mostly much dumber than that.

What follows are some brief thoughts on the functions most visible to those of us civilians who do not currently use AI in our workplaces.

Writing Papers

This, as you may remember, was the number one panic upon the release of ChatGPT last year. The kids are going to cheat in school! They aren’t going to carefully consider the themes of To Kill A Mockingbird! No one wants to work anymore!

The moralizing tone of this argument fell somewhat false to my ears. From where I sit, it seems that the American school system has recently graduated many thousands of students who could not write a passable essay. I’ve been in college classes with these students, discussed their efforts with my peers who are their professors, and read casual American writing on the walls of the internet and the verdict is in: we are already not learning to write well.

When I helped a friend dissect a pile of student reflections to determine which were likely AI and which were organic, the biggest tell wasn’t the predictability of the content of the essay, but the predictability of its syntax. ChatGPT might write, “The 2013 film Her examines the universal challenges of human connection through the speculative lens of artificial intelligence,” but only a student would write, “Her is about a the danger of falling in love with a robot and the interesting questions about that such as ‘what is love?’ and ‘is technology good or bad?’ All in all, I thought it was kind of weird, but ok overall.” We also noticed the tendency of the software to produce bulleted lists, and these appeared in nearly all of the AI-aided student work. She chose to confront these students—they all fessed up—and offer them another opportunity to complete the assignment.

Ultimately, this particular problem is one for educators to solve, and they are doing so in a variety of ways—some forbidding the use of AI tools, some structuring acceptable use, and some encouraging it wholeheartedly as a function of practical learning relevant to the future/present workplace. I am not an educator, but I am a writer and a reader. I find writing to more useful as an engine for thought than as a means of communication or self-expression. That process of discovery is what people using ChatGPT to write miss out on, and that is a personal loss for those minds more than it is a collective loss for we, the readers.

Ted Chiang shared similar thoughts in his 2023 piece, “ChatGPT Is A Blurry JPEG Of The Web”:

“If students never have to write essays that we have all read before, they will never gain the skills needed to write something that we have never read…Some might say that the output of large language models doesn’t look all that different from a human writer’s first draft. But again, I think this is a superficial resemblance. Your first draft isn’t an unoriginal idea expressed clearly; it’s an original idea expressed poorly…”

As for me, I would take a world of original ideas expressed poorly over the bland consensus of unoriginal ideas expressed clearly any day, bad grammar and all.

Making “Content”

I think that most of you know what I mean by “content,” but it’s a slippery term. The worst couple of definitions I found describe it as “information presented with a purpose distributed to people in a form through a channel” and “any creative output designed to engage, inform, educate, or entertain an audience through various mediums.” With all apologies to Content-Whale, the source for the latter definition, I disagree. By those definitions, novels and records are content. Porn is content. The Sistine Chapel is content. Even this newsletter, the closest example on this list to “content,” given that it’s distributed online and packaged in a consumable fashion, is NOT (primarily) content. If someone describes themselves as a “content creator,” you should challenge them to a duel.

Here’s what I think distinguishes “content” from other forms of art, media, communications and advertising:

content (noun) 1. Any creative or generated output (written, visual, audio-video, interactive) designed to generate revenue via monetized engagement either a) directly, through vector platform pay-outs, paid sponsorship and other one-to-one compensation or b) indirectly, through the cumulative impact of audience growth and retention, potentially feeding an algorithmically driven feedback loop. 2. Any form of cynical clickbait, SEO language padding, or other material existing primarily to drive or retain traffic, often derivative and easy to mass-produce.

Phew. “Content” as relates to AI takes varied forms, many of which were listed in the introductory post of this series. The slew of AI-generated content whether in the form of memes, bizarre images circulated through bot networks by click farmers, or junk books clogging Amazon, is now being commonly referred to as “AI slop.” What I find interesting about the slop is that it’s composed of the remains of previous human-made iterations of internet garbage. A sort of nightmare information compost, if you will.

That old garbage was what had already rendered Google and other major search engines borderline un-usable in the years leading up to our more recent AI breakthroughs: search engine optimization (SEO) and the emergence of content mills. In short, SEO is a way of writing content for the web that makes a site more deeply indexed and easier for the crawlers of a search engine to find. Not inherently evil, but as the professionalized field of SEO grew, so did the long preambles to recipes that drive us all up the wall. More key words, more opportunities to be surfaced on the hallowed first page of results.

Content mills utilize low-wage freelance writing labor (and, increasingly, AI-generated text) to create SEO writing and other content for various online platforms. Websites that pop up toward the top on search results but don’t seem to be connected to a clear institution, publication, or group of human individuals? It’s very likely you’re enjoying milled content. Yum!

In the past, much of this content has been competently written and moderately researched (by the aforementioned freelancers), but as we tread further into the hallucination-prone generative AI era, that’s no longer something we can expect.

Search

Due to the just-described, search is further deteriorating. I’ll use Google as an example, since they are our verb for “search the web”. The once-prized front page of Google results is clouded with Sponsored links and SEO garbage, lubricating the slip and slide right into Google search’s new frictionless AI integration. I usually don’t use Google search, but when I did for a week or two while working on this series, I found the AI blurb tantalizing. Like texting ChaCha and getting a single, uncomplicated answer. If you remember texting 242-242, you should consider incorporating weight-bearing exercise into your routine, as your bone density has begun to decrease.

Pattern Recognition, Prediction:

Pattern recognition and prediction are the primary functions of large language models. They recognize patterns of language and image and then use the material upon which they’ve been trained to predict responses to prompts. Chatbots who can hold a passable conversation (and flirt!), generative fill tools that can “imagine” what’s happening outside the frame of an image, custom synthesis to emulate individual human voices.

Outside of those examples, and other obvious—some potentially groundbreaking—possibilities (diagnostic support for human doctors), I find the behavioral applications most troubling. Here be more troubles readymade for AI to accelerate.

When we talk about “The Algorithm,” we’re talking about proprietary, often shadowy, software that observes and adjusts to human behavior and engagement with a product or a real-life surface. Dating apps that know your preferences and serve up someone just your type at the moment you’re disengaging—about to put your phone down, Spotify’s “curation” of playlists for your every particular moment—your “Matcha Girl Downbeat Tuesday Afternoon”— or “social” apps that close deals for their actual clients by feeding you ads for a trinket you once considered buying, and the raw, addictive, slot machine power of the recommendation engines of TikTok and Youtube, to name a few.

[This post from a few weeks ago discusses “the algorithm” and the pleasures of avoiding its lure in depth.]

Perhaps the most universally engaged predictive programs in our lives arrive in a more helpful package: the blue lines and calm verbal cues that guide us on our commutes and other explorations. A caveat here: I rarely use Google Maps and have never downloaded Waze, not because I’m an annoying Luddite elitist, but because I live in the rural American West and essentially…make very few turns. Traffic issues include massive, slow-moving farm equipment blocking a single lane, livestock hazards, and slow moving day-trippers afraid to take our highway curves at local speed.

I also just like maps. Some of my most pleasant car memories involve helping my dad navigate to estate sales using his giant street atlas of our city and its surroundings while he drove. Because I live somewhere where you don’t have to drive far to lose reliable cell coverage, I still keep both Washington and Idaho road atlases in my car. In a very classy move, I did not brag about my affinity for maps, nor point out the irony of the situation, when a dear 70-year-old friend of mine panicked at the start of a trip when she couldn’t get Waze to connect. “I’ll be FUCKED!,” she fumed, smashing her touch screen in uncharacteristic rage.

For all my trepidation about Google’s monopolistic power, I love Google Maps as an exploratory tool and as an archive. I’ve used it for art in the past, and use it for memory-jogging and research in my writing practice today. Surveillance concerns aside, I find it kind of amazing that the world’s landscapes and city streets are visible and virtually walkable to every web-connected person on the planet.

There’s nothing fundamentally “wrong” about using this technology to get from A to B and it especially makes sense for people working in delivery or other driving-centered jobs. Ditto the stressful driving my septuagenarian friend anticipated facing without Waze. Sure, she grew up with paper maps, but now seldom drives alone, and today has to navigate a labyrinthine system of intersecting freeway exits, tolled and non-tolled routes, confusing signage, and so forth. What gets to me is people who use these apps every time they are in the car, even in their home towns and familiar cities. The integration into new vehicles often removes the choice to use GPS altogether.

Waze in particular focuses on using network-sourced (from fellow drivers) real-time data to optimize your drive, saving you seven minutes, say, on the way to pick up your daughter at practice. Many of the wide-eyed pitches being made about the magical future AI promises us center on this same philosophy: outsource your menial tasks to time saving “sidekicks” and optimize your life. I am as brainwashed by productivity culture as the next young white woman who was told I was dangerously “gifted” as an eight-year-old, but I still feel deep in my soul that app-driven “optimization” is an absolutely brain-dead way to live.

Comedian Pete Holmes summed these feelings up for me in a rant on Adam Carolla’s show (which, yes, TikTok served up rather auspiciously). God help me for quoting “content” from the platform of one of the “you can’t say anything these days” middle aged white male comedians (co-creator of The Man Show, no less), but Holmes does open by telling him to “eat fuckin’ shit,” so maybe it’s a wash?

Holmes says, “The idea of Waze and a lot of these time-saving fucks are taking us away from the opportunity we have to sink and surrender into the happiness that we are, instead of this circumstantial happiness that doesn’t work…[once I get out of this traffic, I’ll start really living]…It’s a lifestyle choice, surrendering to traffic, surrendering to your life, surrendering to reality. It’s in the Tao—they say, ‘the great way is not difficult for he who has no preferences.’ So [Waze] is the thinking mind made manifest and grotesque…”

And speaking of grotesque…

Art and Design

Since this is probably the most think-pieced aspect of recent years’ AI developments, and because this piece is already sprawling (nice to see you’re still here ^_^), I’ll leave this one hanging for now. A poet friend and I began to probe this topic the other day and many fascinating, maggoty aspects emerged to examine. One I want to chew more and write more about in the future is the feeling that a significant faction of “tech guys in charge” simply sort of hate (or at least resent) art and artists. Is it our frivolity? Our ability to imagine for imagination’s own sake, outside the profit motive and without creating a self-serving mythology of altruism to justify our making?

And, finally…

Surveillance

I referenced Clearview AI in the introductory post to this unwieldy series, and I still recommend you listen to the podcast I mentioned then, or that you read some of Kashmir Hill’s in-depth reporting on the company and the alarming development of the open source facial recognition industry. But as a quick review, this company created a highly effective “Shazam for faces”—Shazam being a popular app that identifies a song by just a couple notes or bars picked up by your phone’s microphone—but, don’t worry, they only let cops and other trustworthy clients use it. Cool!

Of course, the underlying technology has become increasingly accessible and since it’s fundamentally pretty uncomplicated, there are now many versions of similar technology available to anyone with—in the case of one popular alternative—$28 to spare. Combine this reality with the increase in mask bans across the United States (a dual horror for those of us still covid-cautious, looking down the barrel of forever isolation in a society drunk on pandemic denial and eugenics thinking), the proliferation of cameras throughout our lives (the networks of Amazon’s ubiquitous Ring cameras, already lent out to police forces around the nation), and the generalized normalization of surveillance (face scans at the airport, which are not yet required but heavily encouraged), and it’s…pretty bad.

AI facial recognition will only, under our current power structures, increase the power of the state and capital to invade our most private spheres—adding the arrangement of our bones and the marks on our bodies, to their pretty good guesses about our innermost desires.

I don’t know about you, but I can’t wait for Season 28 of Law and Order: SVU when Benson starts using Clearview AI to ID perps and stalk them on social media! As I write this, I realize there’s a 50/50 chance that’s already happened on SVU.

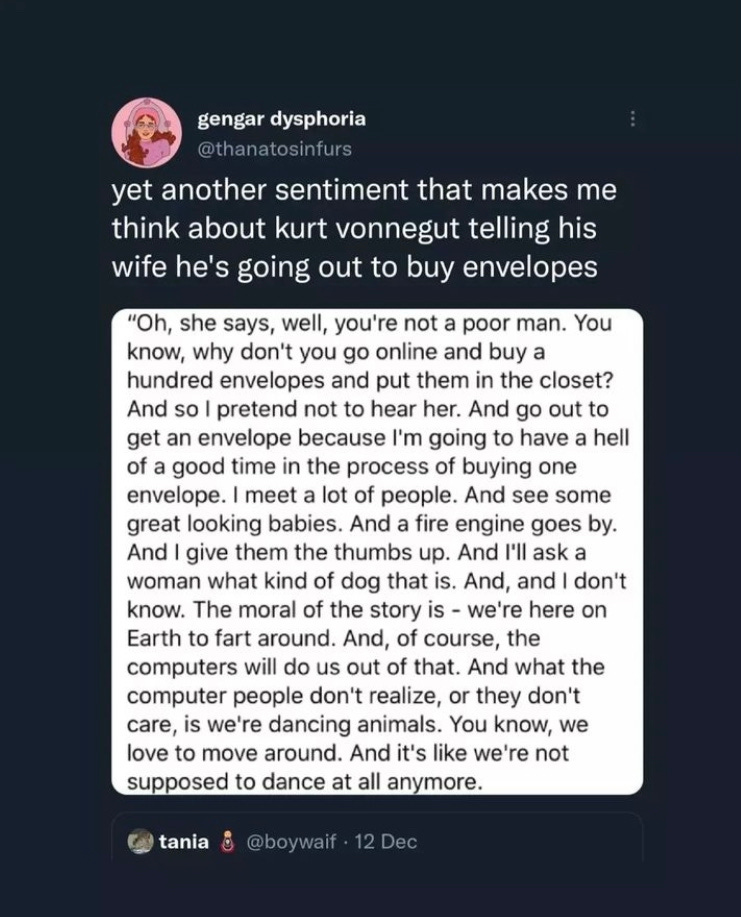

Next week, we’re on to Value. What is AI worth? What social, economic, ecological, political value does it hold? Until then, Kurt Vonnegut:

<3

TRW