Lord, let me not become a Brand

thoughts on leaving social media (again, and only sort of) as i welcome you to a new iteration of my digital presence.

“I think we’re seeing…the implications of telling people that because they’re not going to have a job and they’re not going to have a pension, their lifeboat in these roiling capitalist seas is their personal self. Their optimized self.”

-Naomi Klein

I started an email newsletter two years ago as a stopgap—a way to stay in touch when I left social media again, inevitably. Over the past fifteen years, I’ve scrubbed or overhauled my social media presence many times. Just this week, I stripped down my Instagram account yet again as a way to shift focus to this incarnation of a newsletter, on this new-to-me tech platform I’m choosing to trust (I guess) for now.

Before this latest scrub, there have been post-breakup redactions, unflattering photo tag removals, hard deletions during paranoid episodes, platform migrations (RIP my LiveJournal, MSN Messenger, Myspace, Tumblr, Facebook, and Mastodon accounts), alternating periods of dormancy and earnest over-use.

I have a downloaded archive from my final Facebook deletion about five years ago. I also have a handwritten, ancient address book that I made five years before that when I deleted Facebook for the first time, in preparation to travel to Palestine. I was told at the time—accurately—that my social media accounts might be checked upon entry to Israel. My phone number hasn’t changed since I got a phone in the eighth grade (gasp) twenty years ago, so I also still possess every contact I ever saved.

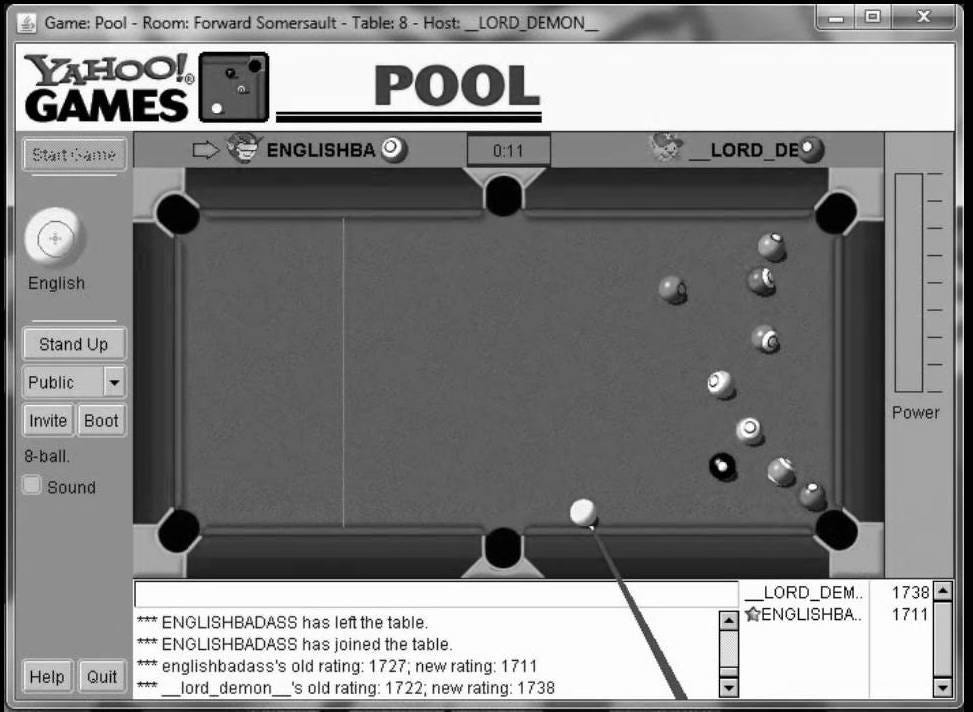

This digital network and record, imperfect, but still partially preserved in my own care outside the cloud. And somewhere out there, a perfect image of a version of myself that I’ll never own, built of every bit of data I’ve fed to these machines since I first started catfishing in the Yahoo! Games pool hall as an eight-year-old.

For a few years now, I’ve been hearing about the End of the Social Media Era. It feels more accurate to say that rather than “ending,” it’s morphed into something else, the way we interact online via privately held platforms. Something bigger, and perhaps less social, than social media, but too conceptually amorphous to name. The pundits who speak of this change—whether with enthusiasm or dread—seem to agree the transition of epochal power has something to do with the collection of technologies we refer to in aggregate as “artificial intelligence.”

The form of AI that has everyone worked up at the moment is a so-called “generative AI.” While the publicly accessible forms of this tech may appear creative, sometimes with results that are rather eerie, it is essentially just collaging our own most frequently expressed thoughts into arrangements that appear new. This process reveals fascinating truths about the dominant culture of internet users and artists that culture has seen fit to digitally preserve.

As Latanya Sweeney, director of Harvard’s Public Interest Tech Lab, explained in a recent interview by Krista Tippett for On Being, this public sourcing of generative AI chatbot ChatGPT’s knowledge base means that teams of coders have had to build a layer of interface between the raw program and its user public. The bot’s propensity for misogyny, racism, and otherwise offensive content is as high as you might expect it to be if you’ve spent much time online. And little programs, it seems, have big ears.

Much of the handwringing about generative AI has felt misplaced to me. While there are real concerns about its amplification of our ability to spread mis-and-disinformation, the underlying issue there feels separate from the technology. Amplification is the key word. Like a child who screams when they’re screamed at, we, the progenitors of this tech, are the culpable party. To be more generous though, ChatGPT learned from the worst version of “us”, a version that learned to behave a certain way in a new technological environment during a period of unending social experimentation, so no one’s been at their best.

Students are, of course, using this technology to cheat. A professor in my life has been recently discouraged by her students using ChatGPT to write their reflections on the films assigned in their Intro to Digital Cinema class. It’s a fun class, an easy class, even—compared to some of the more strenuous film classes I took as an undergrad—and it sucked for her to feel that they didn’t care. I had fun helping her evaluate the suspects’ written responses. I helped vindicate a couple of the students who delivered boilerplate about the films like a bot might, but revealed their authenticity through good old fashioned bad writing. Their unusual compositional choices felt “real” because they were—grammatically and syntactically—“wrong”.

Sweeney points to this same phenomenon of novelty as a hopeful note for creative people who worry their life’s work has already been cheapened by this technology. She responded to Tippet’s question about this, saying,

“Now hallucinate as it might, it’s not likely to bring those connections together…the things that are said 90% of the time, it’s going to say it. It’s going to hallucinate to connect one 90% to another 90%. But it’s the unusual pieces that hold the idea — that’s not going to really happen. It might happen once in a while, but it’s not going to happen regularly.”

Hallucination is the word technologists have attributed to the “thought” of generative AI systems. It’s what the program does when a direct answer is not obvious—it “imagines” a likely connection between what’s been asked and what it’s already discovered a user wants.

So Sweeney posits that mostly, for now, this technology will be great at regurgitating the themes of a film you were supposed to watch in class, culled from the consensus points of every academic paper and critical review about that film it can find online, but it is less likely to do the original work that writers and artists do—the labor of finding connections between seemingly incongruent topics and quilting new meaning into them using the thread of our unique lived experiences. It won’t know, for example, to respond to cheating students with not only empathy, but with a poem.

Anyway, I’m sure this isn’t the last time I’ll write here about AI, but I came to write to you about social media. While we struggle in real time against the limitations of the communication infrastructure we’ve co-created and inherited, it’s still necessary for some of us to keep a foot in the door. I don’t plan to feed the machine as many of my own thoughts, and I hope to revoke my image from its servers as much as possible. But I’ll be there to partake in other ways. Issues aside, it really is incredible to be so connected, particularly (horrifically) in times of violence and crisis and protest and uprising.

There are deep issues with the simplistic attitude of distrust for establishment media in our culture, and at the same time there is something to be said for placing a camera and microphone in the hands of normal people on the ground. Even outside of observing the catastrophic truths of colonialism as so many of us have been over the past weeks, it’s nice to be reminded that other people are out there.

As someone living in a rural, racially and culturally rather homogenous place, it’s a breath of fresh air to be able to get on TikTok or Instagram and see comedy, analysis, art, and daily life from people different from those to whom I spend my days in proximity.

But now, the beef, in brief. The reasons why, with minor exceptions, I’m going dark on social media once more, sharing less there and more elsewhere.

Beef A: It’s shallow.

I have tried to make Instagram deep. In the poetic sense, by making all of my captions haiku for a while, by bread-crumbing obscure references to see who’s really paying attention to me. In the political sense, by writing long rants into text stories and urging people to action.

Relationally, I never made it happen. I can’t keep track of conversations on a screen (ask anyone I love who tries to text me in an ongoing way), let alone across multiple platforms. Interaction is so reflexive here—tapping the image of a heart, usually, or dashing off a quick comment—that it’s hard to gauge its sincerity.

And of course it’s shallow in the aesthetic sense. Limiting the acceptable range of bodies, imagery and language to reflect a narrow status quo is, in fact, a major task of the algorithm. I’ve realized as I age that I prefer my learning, my entertainment, my relationships deep and slow.

Beef B: It’s performative.

Remember the black squares of white and non-Black Instagram users during the George Floyd protests? And the cycle of backlash to those squares as ineffective, their subsequent removal, the cycle of hot takes about the black squares competing for attention with the very real issues they meant to draw attention towards in the first place? One of many examples of political performance on our social platforms.

And can we always blame people? We’re constantly incentivized to “express ourselves” on these platforms, and sometimes we’re excoriated for our failure to express in a timely manner, or at all. This fault relates to the shallowness of the interaction available on the platform itself, as well as to the hollowing our of our real life opportunities for political, civic, and interpersonal engagement.

Beyond the political, though, sometimes it’s too much of a mindfuck for me to create a digital avatar of myself and perform for…everyone? My friends? My personally assigned FBI agent? Existing on the earth as a woman is a trying enough performance and I find it exhausting to constantly calculate the best way to exist to give the appearance of alignment with my values. It makes me feel like a sociopath. [upside down smiley-face emoji]

Beef 3: It’s surveillance.

The flip side of performance is spectatorship. And anonymous or uncertain spectatorship is voyeurism, at best. On the individual side, the logic of the panopticon can erode our relationships and our self-esteem. Whether we’re monitoring views to see if our crush saw our story yet or if we’re looking at pictures from last weekend when it seems like everyone went out without us, social media gives us access to information we might be better off not knowing! Perhaps FOMO existed before social media, but never have we had such an engine for mistrust and loneliness at our fingertips.

Simple voyeurism becomes surveillance when power is added to the equation. Since social media is so normalized now, it feels like the majority of people have accepted the conditions of mass surveillance we now live within.

If someone walked up to you in 1999 and said “make me a list of everyone you know and how you know them, some background on your most deeply held beliefs, information about where you work, live and study, photos of the inside of your house, a description of what you wear every day, a list of the businesses you frequent, and your thoughts on current events,” you would probably run away from that person screaming. You would at least, I hope, inquire after their purpose in collecting so much information.

Beef 4: It’s a brain casino from hell.

In recent weeks, I facilitated a series of casual Zoom gatherings on the crisis in Gaza. I did this because I couldn’t find any sense of grounding or solidarity on social media. One friend participating described our shared sensation as whiplash.

Scrolling through the vertical feed of Instagram, swiping sideways through its Stories, or upwards through its poor Tiktok imitation, you’ll be confronted first with images of dead and dying children and people pleading for your attention and assistance. Swipe, it’s a funny cat falling off the counter. Swipe, millions of people marching in the street chanting. Swipe, a beautiful young woman implores you to “Get Ready With Me.” Wait, that’s an ad. Swipe, death. Swipe, shop. Swipe, shake ass. Swipe, a flood somewhere. Swipe, a team mascot pulls a prank. Swipe, WORLD WAR 3?? says an influencer. Swipe, nice. Swipe, not nice.

We know that the infinite scroll mechanism added to Instagram when the company now known as Meta purchased it was intentionally engineered to emulate the hypnotic effects of a slot machine. This slot machine from hell delivers serotonin, sometimes, but you have to keep swiping to find it. My brain already fails to make enough serotonin, and I’ve found (shocker) that playing in the brain casino does not improve my condition.

Beef 5: It’s not free.

As everything gets more expensive, I can see how it feels sometimes like staying home on our screens is the only thing that’s affordable to do anymore. And if you are lucky to live somewhere with affordable, consistent electricity and high speed internet, that’s true. But I try to remind myself that these magical devices we carry around do use precious, dwindling resources to operate.

The cloud storage I use isn’t just sitting somewhere in a cloud (what an incredible feat of branding that’s been), but it’s draining the fossil-fuel-powered grid somewhere in the desert, millions of fans whirring to cool it.

Streaming, it turns out, doesn’t really use as many resources as I assumed it might, but I still try to reflect on its impact (even in terms of wear and tear on my phone) as a way to hold myself accountable with my digital habits. A mantra that helped me break my TikTok addiction and get my screen time down has been, “I do not need to burn the Earth’s precious resources to disassociate.” Weirdly, it really helped.

The other resource I think about more as I age is time. When I started tracking my screen time, I realized just how much I was losing to pointless consumption. I would do bad things for an extra couple of hours in the day, especially as someone living with a chronic illness that saps a lot of my physical stamina. To find that lost time and find that it comes with the benefit of improved mental health and clarity has been a gift.

I’m excited to carve out time this month to read Naomi Klein’s new book Doppelgänger, which uses odd, recurrent cases of mistaken identity between her and leftie-feminist-turned-alt-right-star Naomi Wolf as a lens to explore issues inherent to the digitization of our identities. I’m waiting on a copy from the library, and will almost certainly be back here with a full review when I’m done. I did recently listen to her on an episode of the Offline podcast where she spoke about the empty, bizarre feelings that come with turning oneself into a brand.

“What makes a good brand?” she asked.

“I found it troubling to be accused of being a brand as a journalist [because] as a journalist you want to be able to be changed by your research. The people who I trust are people who I know read deeply, report deeply, and are willing to have their mind changed…

To be a good brand is to repeat yourself ad infinitum. A good brand has good discipline, and the measure of a good brand is that you don’t stray from your central message. It seems to me to be a really diametrically opposed mission: to be a good brand versus to be a good human. A good participant in society, let alone a good researcher, a good journalist, a good scholar.”

Hearing this exploration of “goodness” made me consider the issue of performance on social media again, particularly during this era of live-streamed genocide viewed from the insulated center of a rotted-out democracy.

I’ve been posting, as have many others I know, about Gaza, sharing links about boycott and divestment, resources to easily contact representatives, ways to get SIM cards and other needed items through the blockade digitally, and so on. It isn’t because I think it’s the most effective thing I can do, but it’s because it’s something I can do that might help someone else participate more directly. I can’t go to a huge protest where I live, but I can connect to movement spaces virtually and amplify the demands of people on the ground.

This happens to connect to my personal “brand” as an activist, gross as it feels to type that sentence. A friend asked the other night if I thought she “should” be posting about Gaza. She was feeling immense passive pressure to post, but felt that it wouldn’t make a difference. She asked me if I thought she had a moral obligation to post on Instagram.

I had to think for a minute. Finally, I said that we, as American citizens imbued with an undue level of power and visibility on the global stage, have a moral obligation to do something. Extreme violence (as it so often has) is being carried out “in our name and with our money” as the old slogan goes. But I also told her, she’s not a citizen of Instagram. It’s a freaky mirror world that we both feel disturbed to see being increasingly treated with equal weight to the meat world, with its real bombs, and salt, and suffering.

The heightened importance of social media—the perception of the importance of what happens there, at least—might exist in inverse proportion to the amount of power we feel in our daily lives and in our traditional systems. What are we supposed to do, vote? The absurdity of living in this country (probably people all over the globe feel a version of this, too, I imagine) amplifies daily. I understand the urge to create shared meaning online. But these platforms cannot be our society. They’re not a society.

Klein went on in that same interview to address the problem of power that sends people online to become brands.

“I think we’re seeing…the implications of telling people that because they’re not going to have a job and they’re not going to have a pension, their lifeboat in these roiling capitalist seas is their personal self. Their optimized self.”

The optimized self always posts the right thing at the right time, shares their good opinions, takes perfect selfies in natural light, and reminds their friends to do self care. It’s odd to me that so many people on the alleged left have become willing in our landscape to participate enthusiastically in such a deeply neoliberal and hyper-individualistic project.

Posting the same content as your “comrades” does not a revolution make. Yet here we are, and what alternative infrastructure endures? I’ll still be using my stupid Instagram to post about my stupid thoughts sometimes, even though I’d rather live in my little small town dream commune and actualize freedom.

But I need the outside world. I’d miss the exchange of ideas I’ve grown attached to online, so here I am, still pursuing that end. It’s partially because I am a writer, which kind of inherently means that I want to communicate and connect. In all honesty, I also feel the pressure to remain visible to those who might wish to catapult me to fame and fortune (jk…unless…).

Anyway, welcome to my Substack.

I’m excited to be here and this all deeply resonates as I am shadowing myself and limiting my use on Meta products with the use of code, “breaking” the sites so I don’t become completely addicted again. Enjoyed your writing.

If it’s any consolation, I’m 27 and have also been on the internet since I was 8. I write here too, and I love Substack; it’s the slow internet I’ve been craving for a long time.

Wonderful writing. Especially enjoyed this idea of the moral obligation to post on Instagram. What a strange time. btw you might like reading Jaron Laniers lists of social media beefs. Anyway, welcome to Substack! I’m trying the same thing for a lot of the same reasons.