It feels like the year’s gone quickly until I try to remember everything I read. I have to do this by looking back at the scrawled titles in the margins of my planner. Ah, there they are: the novel I crunched through during a couple long days of a dear one’s surgery and recovery, the books I read on my friend’s treadmill watching her sweet senior dog (we love you, Dusty), the paperbacks dampened poolside in the summer and in Mary’s bathtub at the first chill. I’m not a “good” reader, particularly not as a student of creative writing. I don’t read nearly as much as I want to, I’m not as tuned in to contemporary work as I perhaps ought to be, and I don’t put up numbers at the end of the year because, in all honesty, reading makes me sleepy and it takes me a long time to finish even the most compelling book. So, as the year comes to a close, with all those defensive caveats, here is my year in reading.

Mean Spirit, Linda Hogan: When I reviewed Killers of the Flower Moon late last year, I hadn’t yet read this novel. In that review, I agreed with Osage language consultant Christopher Cote’s assessment that Killers was a film most useful for white people to see. He hoped for a telling of the story from an Osage perspective. Because I had just spent so much time thinking about the film when I picked up this book—which focuses on the same events of Oklahoma oil leases, the economic impact on the tribal communities whose land held said oil, and the political violence they faced as a result—I couldn’t help but consider the potential of a beautiful Mean Spirit adaptation. I know Hogan primarily as a poet beloved by a dear poet friend of mine, and as my sister just pointed out to me in conversation this week, there’s nothing like a novel written by a poet. The intertwined worlds of magic and capitalism and the complex, heartbreaking layers of relationships in Mean Spirit have left a deep imprint in my memory. The first book I read in 2024 was the best.

A choice batch of Westerns: As regular readers know, my work is currently focused on the ongoing legacy of settler colonialism in the American West as it unfolds on a personal/familial/cultural level. That research weighted my reading this year toward the Western and epic, particularly toward Montana literature. I could probably spend the rest of my life reading only Montana lit and I’m grateful I was put onto so much of it by one of my mentors this year.

Winter Wheat, Mildred Walker: A quiet novel guaranteed to devastate your everyday Western small town girl living in a lonely world. I simultaneously learned a lot about dry land wheat farming (the bread of the non-Montana region where I live, too) and the conditions of the rural heart. There are scenes in this novel that I think about at least once a week. Walker speaks better than anyone to the bleak landscape that’s written on my very being. With a protagonist who’s roughly a peer of my grandma and her sisters, this novel helped me understand the era (a time somewhat displaced from time and the march of progress by its far-flung place on the map—we see one-room schoolhouses and a lack of electricity into the 1940s, here) that shaped the ancestors of my living memory.

The Sheep Queen, Thomas Savage: After I almost got pulled over for speeding in Montana (you have to try to get pulled over for speeding in Montana, where we are less than a decade out from speed limit signs reading “Safe and Reasonable”) because I was so immersed in the audiobook of The Power of the Dog, I picked up another Thomas Savage novel to see if the magic carried through the rest of his work. It does. Pick it up for straightforward yet musical language and compelling, complex intergenerational family dynamics. Technically an Idaho book, but hey, that’s even closer to home.

Honorable Western mentions:

Bucking the Sun, Ivan Doig (fiction—a mystery-driven drama of brothers and their wives set against the backdrop of the hubristic pursuit of taming the land by building an impossible dam);

Hole in the Sky: A Memoir and Who Owns the West?, William Kittredge (non-fictional musings on family, legacy, and the West that provide a useful recent time capsule for how settler-descended people were thinking about questions of land and inheritance a generation ago. Interesting reflections on Montana literature and myth-making from an insider, heartfelt and beautiful prose, honest emotional inquiry);

Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home, Chris LaTray (2024 release memoir by Montana’s current Poet Laureate exploring both history and personal questions of identity by untangling threads of Metis identity in the West, the mixed outcomes of federal tribal recognition, and his father’s denial of Indigenous heritage).

A choice batch of fiction: I’m surprised by how much fiction I read this year, considering that I always feel I’m reading nonfiction. What it must be is that when I find a novel I like, I blast through it in a few sittings.

Behind You Is the Sea, Susan Muaddi Darraj: A novel-in-stories, this is one of those that flew by as a result of my deep immersion in its characters’ worlds. Intertwined stories of Palestinian diaspora families living in Baltimore (with a final chapter taking place in the West Bank) span themes of family, class, duty, power, love, lust, and home. At times it made me laugh out loud and I was frankly furious when it ended because there was so much more I wanted to know about these characters’ lives. I was thrilled to work with Susan as my first MFA mentor in the semester before this book’s release. She’s a hilarious, bold, shrewd, and warm writer. Even without that personal connection, I’m quite sure I would have loved this book.

Love the World or Get Killed Trying, Alvina Chamberland: June brought this one back to me from Berlin in late spring, chaotically signed with a scrawl that matches Alvina’s somewhat stabbing prose. I suppose this is auto-fiction, an excellent companion for traveling, a stream-of-consciousness ode to all the title suggests. The austere beauty of Iceland, the daily turmoil of dating-while-trans, the burdens and wonder of “feminine emotional intensity”, the small satisfactions of solo travel, diatribes against our technological hell-reality (hello, my app-hating sister across the ocean), all collide unified by a captivating voice. Here’s a quote I dog-eared (one of many): “Yes, I suppose writing always entails the possibility of taking notes that you’ll later enter into that Google thing that in fact systematically searches you…Ugh, this thought turns my mood towards darkness. I cling to my feminine emotional intensity, as it may be the sincerest form of resistance to our cold, digital world of apps, facts & fake facts.”

Centerville, Karen Osborn: Karen gave me a copy of her novel Centerville while I was in residence at my MFA program this summer. Since I am not studying fiction, I will not have the opportunity to study with her, but as we are both immune-compromised, we (she, me, and her dear husband) shared every meal outdoors under the large wedding tent. In Karen, I found a kindred spirit—a real weirdo, a sensitive soul—and in this novel I found an incredibly well-developed small town of characters rocked by an opening-scene tragedy that was probably one of the best opening passages I’ve ever read. The explosion that sets the plot in motion is described so beautifully that it still returns to me, unprovoked, many months later, as though it had happened in my own life. A gem.

Minor Detail, Adania Shibli: The senseless violence of the state, the destabilizing force of occupation, and the mysterious drive behind individual actions are all captured with a subtlety that complicates the simple surface of this slim novella. This is a difficult read for the violence at the center of the novella’s two intersecting parts, but a must-read for anyone who wishes to explore the dulling psychological impacts of war (war?). For me, stomaching the first half—which focuses on a feverish Israeli soldier at a far-flung outpost whose detail captures and eventually kills a Bedouin Palestinian girl—opened up space to inhabit the second half, focused on a Palestinian woman’s obsession with researching the case, many years of occupation later. The mounting dread of the entire work builds to a breathless conclusion. You don’t have to understand everything about Israel and Palestine to inhabit this small book, and it may help you understand more without belaboring the historical details through which it wanders.

Best Of Memoir: I read ten memoirs this year (and have nearly finished an eleventh!) and would particularly like to hear your recommendations in this genre as I move into my thesis semester and have to, like, you know, write a memoir.

Mourning Dove: A Salishan Autobiography, Mourning Dove: As I read this book, I kept wondering why I hadn’t read it sooner. The work I’m engaged with has forced me to examine my own education at length, and the omission of Indigenous stories is the most glaring theme in that educational reflection. So I include this book not only because I enjoyed it, but because I learned so much about the place I’m from (Christine Quintasket aka Mourning Dove was of Okanogan, Lakes and Colville heritage—some of the people who were the First to live where my family would later settle) that I should already have been taught. In addition to learning some of the stories, practices, and history of this place, I appreciated the conscientious editorial touch Jay Miller’s notes throughout the text, which offered expansion and clarification while being careful to preserve the author’s original words and intent.

Inherited Silence: Listening to the Land, Healing the Colonizer Mind, Louise Dunlap: Bill recommended this book to me when I told him what I was working on. And since Bill has taught me more about how white people can learn to work beyond our violent racial inheritances, I listened. This is a rather dense book, at times over-dense, but still a worthwhile deep dive into the truth of the Northern California land beloved to its white, settler-descended author. Dunlap has done her research and laid out her prominent family’s direct involvement in the settling, unsettling, and re-settling of this land, but more importantly, she has done (and, impressively, documented) the complicated emotional work inherent to unlearning the mythology of white supremacy. She holds empathy for those, like her mother with her garden of native plants, who did the best they could with the knowledge they had, while also refusing to excuse or explain away the horrific violence that is always with us on this land. Recommended to all white folks, particularly in the West, who wonder what it might really mean for us to respond to calls to “decolonize” or support Land Back movements.

Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir, Deborah Miranda: A perfect companion read to the above suggestion, Miranda’s new-classic memoir is a must-read for anyone in the state of California and the greater American West. Again, it’s one I’m embarrassed I hadn’t read sooner, and I’m grateful to Jaimie for throwing a copy in the mail for me for no particular occasion. I’m only about two-thirds done, but I love Miranda’s tongue-in-cheek style when addressing the California tradition of the K-12 “Mission project”, her honest treatment of her imperfect family, and the incorporation of poetry, including erasure poems salvaged from primary source documents. This book is both a juggernaut of the genre and an engaging, fast-paced read about some of the most disturbing (and normalized—see: the “Mission project”) violence in our nation’s history. Read this book before your kids get to their 5th grade “Explorers” unit, or whatever your region’s equivalent might be—it will equip you to engage honestly with the glossy narratives we’ve inherited.

If the previous three books can be considered a triptych on learning and unlearning the mythology of place, then the following three (not all strictly memoir, but all in the general vicinity) can be considered the triptych that drove my work this past semester—a shockingly book-length essay (in progress) that works through a collection of archival photographs.

Plainwater: Essays and Poetry, Anne Carson: I had been told to read Carson’s Short Talks in the past, and then my dear poet mentor this semester assigned me one piece from that collection. When I responded to it, she sent me off to read all of Plainwater, which contains a few shorter collections of poems and essays together in one (delightfully primary-colored) volume. From Carson, and from the language of poetry more broadly, I was nudged into the terrain of strict form, of rules to follow that might paradoxically open up my own self-permission to the writing I needed to do. While this collection might not be for everyone, I believe there are at least a few lines within for anyone. Carson’s work with structure gives a diaristic feel to sprawling, abstract work that might otherwise feel unwieldy. I have to say that “On Waterproofing,” the first assignment, is still my favorite among the Short Talks.

Woolgathering, Patti Smith: When I first met this semester’s aforementioned mentor, Carol Ann Davis, she told me an intensely reassuring anecdote which featured Patti Smith. You can imagine my thrill when she recommended I read her this semester because of the direction my work was headed. No pressure. Having read her more visible books (Just Kids, M Train) in adulthood, I was pleasantly arrested by the quality of this much earlier (1992) work. A series of interlocking and related prose poems, it follows a curious artist-child through the mysterious terrain of memory, evoking incredible images at every turn. If you, like me, struggle to remember your childhood and wonder what it was all about, allow Ms. Patti to take you by the sticky hand and drag you through her fields.

Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes: When I began (reluctantly) to write from photographs and about photography this semester, I plucked related books off of my household’s shared bookshelf. When one half of the bookshelf comes from a photographer, it comes better equipped than average. That said, she kind of rolled her eyes when I pulled this one down. Was it old fashioned? Unfashionable? I meant to flip through for a few notes, a jumping off point or two for a little essay, but I ended up reading the entire slim book in a couple of days. Barthes zooms in and out on the whole of photography—widening to take in its entire scope as a project, then narrowing in on a particular image of his late mother as a child. Back and forth, it continues, meditating on death (as all photographs represent a moment of death, the death of that singular moment), power, magic, and the rest. Was it just the right time for me and this book? You tell me!

Best of Nonfiction: I read surprisingly little non-memoir nonfiction this year (perhaps tuckered out from Doppleganger and all the AI research?) but what I did read, I enjoyed. Particularly in retrospect, I appreciate the way my favorites spread all the way across the map from science to research narrative to true crime and back again.

Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, James Bridle: My introduction to James Bridle was through reading their first major book, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (yes, a very uplifting title), which hooked me on their inquisitive outlook and quick mind. Ways of Being (which also, I think in its UK edition, bears the better subtitle “Beyond Human Intelligence”) had a bright cover and a compelling blurb, so I bought it on a visit to Powell’s. I must say, I don’t remember many of the details of each chapter now, though the book was positively packed with fascinating research about the utopian history of computing, about animal cognition and self-recognition, about plant communication, about the use of art as a tool to exploit and explore the limits of tech. What I do remember was the uplifting nature of Bridle’s affirmation of mystery as a social good. They formed part of the thesis of my own work exploring AI this year: the best humans have to offer in this moment of technological expansion and planetary collapse is our humility. Thinking on a species level helps me when I get stuck in my own culture’s baggage of separateness—race, gender, class, sexuality, etc.—and perhaps thinking of ourselves as one species among many, one intelligence among many, may help us out of our many other quandaries.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot: I missed the train on this one during its hype-cycle shortly after release. I remember the NPR interviews, the film adaptation, but perhaps for that visibility, I passed it over. When a mentor recommended it to me as an excellent example of research narrative, I’ll admit that the hype had deflated my expectations. Are things that people like actually good? Yes, they often are, you snob! You don’t need to be considering the question of self-insertion as a researcher-narrator into your own work to admire the elegance with with Skloot inserts herself into the story of the Lacks family. Her own presence as a white outsider attempting to connect to a Black family so abused, underestimated, and ignored by medical, legal, and financial systems underscores and exposes those events in a human way. We aren’t drowned in statistics, we’re thrown into the middle of a story where it makes perfect sense to slam the door in a white lady’s face when she shows up asking questions, to hang up the phone again and again. Also, I learned so much about medical research and cancer treatment, alongside the family of Henrietta Lacks, the woman whose cells made so much of that research and treatment possible.

When the Moon Turns to Blood: Lori Vallow, Chad Daybell, and a Story of Murder, Wild Faith and End Times, Leah Sottile: Ok, these subtitles are out of control, but authors don’t choose them, so James and Leah are forgiven. If you are interested in the far-right and extreme belief in general, you should be reading Leah Sottile. I was lucky to reconnect with her this spring when I interviewed her for my zine about fry sauce (the Inland Northwest’s condiment claim to fame) and white supremacist belief in our region. We met when I was a little baby wannabe journalist and we’d frequent the same house shows. I was so flattered she remembered me, let alone agreed to be featured in my wacky self-pub about the intersection of mayonnaise and extremism! ANYWAY—this book. I picked it up impulsively after our interview when I noticed it on the shelf of my local library. Then, I started reading it and didn’t stop until I reached the final page five hours later. Is this why people read true crime? I wondered. But no. I think what I loved about this book—Sottile’s sensitivity—is too often absent in the genre. In approaching the horrific crime at the center of the story, there isn’t voyeurism, but genuine intellectual curiosity. What makes someone believe that the end is nigh? What drives some to believe so fervently that they will destroy lives (literally) in service of their delusions? Next up this spring: Blazing Eye Sees All… which you can pre-order. She also has a great Substack.

Finally, the best of Nostalgia: It all started last year when I needed help getting to sleep and finally downloaded the Libby app. (What? You don’t have the Libby app? It’s a wonderful way to access and support your local library! Get it together!) I didn’t want to fall asleep listen-reading something too engaging, too high-stakes, so I started to search for the books I loved best as a child. Cue Madeline L’Engle. Cue Judy Blume, Laura Ingalls Wilder and the GOAT Sharon Creech. So maybe I’m addicted to falling asleep listening to Nancy Drew now, but that’s between me, my God, and my “pleasantly plump” friend Bess.

Dear America: Voyage on the Great Titanic, Ellen Emerson White: If you know, you know. Yes, these are the formative millenial staple series with the ribbon bookmarks that match the color of the cover and binding. Yes, they are elegantly hardbound with thick, quality paper, indicating respect for your twelve-year-old care and intelligence. Yes, Dear America is the iconic series of historical fiction that raised so many of us, sneaking history lessons in through the narrated lives of twelve-year-old girls across time. I think that I read the Oregon Trail one (Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie) this year, too, but can’t say for sure so it didn’t make the list. But this one, the story of Miss Margaret Ann Brady, a simple London orphan who gets the chance of a lifetime to travel on the Titanic as the companion of an old rich lady, was the one. I was a Titanic freak from the time the movie dropped (I was six? And I got to see it in the theater like, three times??) and this was the perfect continuation of that obsession. Honestly, it holds up, introducing incisive class analysis in an age-appropriate tone, witnessing the realities of child labor and rapid industrialization, and, of course, warning of the hubristic tendency of man.

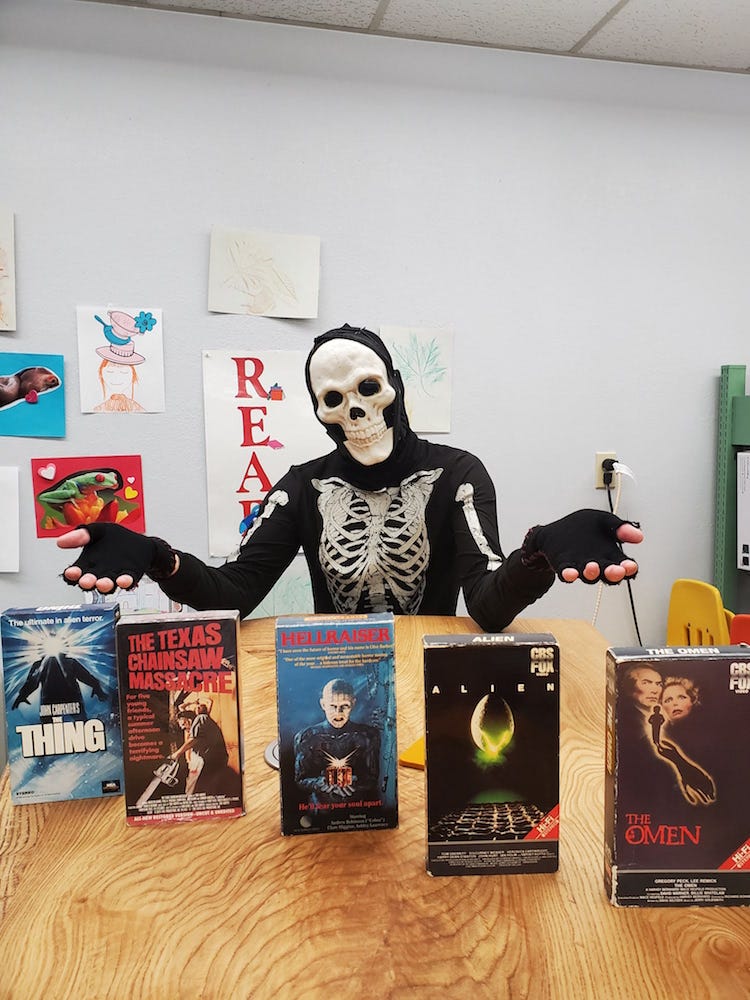

Sideways Stories from Wayside School, Louis Sachar: While substitute-librarian-ing in my tiny town, one of the quiet fifth-grade boys shuffled through the Juvenile lit section. I asked him what he liked to read and he said stuff from shows, adventure, all kinds of stuff, he guessed. I joined him in the aisle to browse and saw the familiar spine of Holes, waiting. I said, “This was one of my favorite books when I was your age, and they made a movie out of it.” He gave me the look of “but you’re old,” and politely asked what it was about. When I told him it was about a mystery at a child prison camp where they have to dig holes in the desert all day, I received the rare gift of a raised eyebrow and a smile. “That sounds…dark?” he said. But he checked it out and when I returned to the aisle later, I saw another familiar spine, now leaning in the “S” section. We all read Holes, but did you also read Wayside School?

Holy shit, y’all, the way my soul jumped out of my body when I saw the illustrations. I must have owned this book or checked it out so many times. And yet, I couldn’t have called it up if you’d asked me what I liked to read as a kid. But it is still so good. The best children’s authors respect kids’ intelligence and Sachar is a sterling example of this. Now, as a student of writing, I can see the way that respect for his audience plays out in creative formal choices. One story is written backwards, line by line, beginning at the end. Another explores the paradox of the school’s nineteenth floor (which does not exist) as a student gets temporarily stuck there, wondering how to escape from a place which does not exist. The stories are also deeply subversive, as in the chapter “Free,” where little Milton, who loves to sit in his chair at the window and watch his bird friend fly past, realizes that he (at his desk, answering to bells all day) is not free himself. He escapes to the basement (where the dead rats live…the DEAD rats LIVE, you guys) where strange men with an attache case approach him and allow him to sign a contract granting him freedom. He goes back to class and sits on the floor, because he can. I could go on about these stories forever, but highly recommend them if you have younger people in your life, or as a trip down memory lane.

And by the way, that fifth grader returned Holes a couple weeks later. When I asked him what he thought (in front of his friends, no less), he grinned, nodded, and let me know that “it was actually pretty cool.”

Keep reading in the year to come. See you on the other side. <3

I am always so delighted to read your thoughts, and I am especially grateful for this offering <3

Great recs !