I don’t know about you, but I need a break from the AI talk. Particularly as a near-year of genocidal terror escalates into full blown war, I want to a dispatch from a softer side (as soft as I get, at least) of my work this week. For reading and action on this week’s escalations, please see the link list at the end of this post.

I haven’t had the dedicated time to complete my “Big Dumb Gold Rush” series over the past month or so because I am deep in work on my thesis project. Folks seemed to like the last research wormhole I put up early this year, so I thought it would be nice to share some of what I’ve been immersed in for the past couple of weeks.

Deep in research on a specific branch of my family tree and their 1880s Montana context, I’ve been most drawn, lately, to photographs. In August, I spent a weekend with my cousin scanning albums I didn’t know our aunt had, full of old, old photos—names we slowly placed on the family tree. We had fun on genealogy websites, tracing various folks as far back as we could, groaning when they led back to England, seeing who could travel back in time the furthest (she won, finding a named ancestor born before the year 1,000). The album itself was bound in 1897 and opened with a strikingly contemporary sort-of meme.

B.F. and Erna are my great-great-grandparents, and those must have been some carriage rides, because in 1898, she agreed to leave a comfortable life in Iowa to join her much-older husband in a far-flung part of Montana that would not be accessible by train for another six years.

I love photos like this one that are formally strange or that otherwise deviate from our stereotypes of serious-faced portrait photography at the turn of the century.

As I’ve written here before, Montana state history is perhaps especially well-preserved. Luckily for me, this includes extensive photographic archives of Central Montana at the turn of the century. These are useful to parse when searching for particular information about my family and their greater community, but also incredible tools for general inspiration. Under my current mentor’s suggestion, I’ve begun keeping a list of “artifacts”—objects, ideas, phrases—that I can weave throughout this work and many originate in this archive. Those are a bit too abstract and yet under-cooked to share here, but I love the photo below of my great-grandmother (B.F. and Erna’s daughter, Zelma) and her “women’s gymnastics” class in 1918.

One of the most fascinating photographers of the American West I’ve been introduced to during this research is Evelyn Cameron. I happened upon her work browsing an unruly country museum bookshelf crammed with pamphlets and ephemera. On the cover was the self portrait below. How could I resist?

Cameron is interesting to me because she, like Erna, left a comfortable “civilized” life (though Cameron came to Montana directly from England, from the highest ranks of society) for a rougher life out west. She developed an interesting, playful style as a photographer, largely teaching herself technical skills and composition. Her earliest work supported her husband’s ornithological studies and she set up bold, dangerous shots to capture intimate views of eagle nests. From there, she branched out to other subjects including the wild animals she and her friends attempted to tame and the cowgirl friends she made among neighbor ranchers.

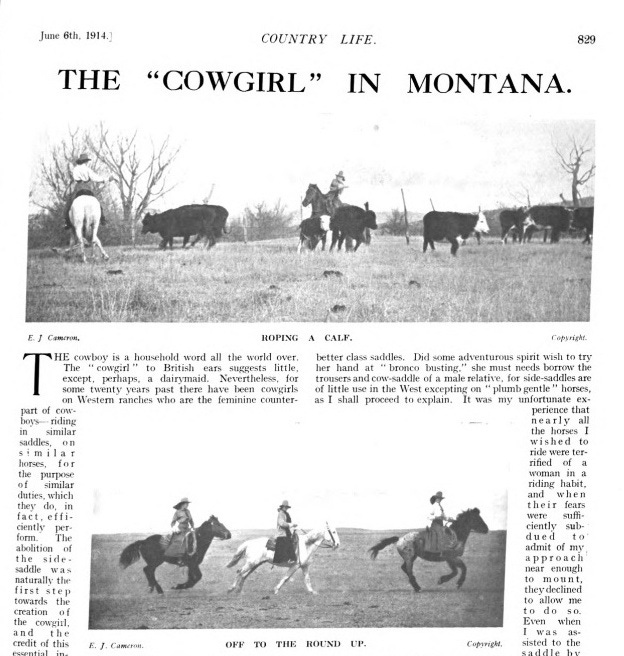

Writing home, in a sense, to Country Life magazine in 1914, Cameron bridged the gap between upper crust ladies in England and the new way of life she’d found in Montana. Her photo essay “The ‘Cowgirl’ In Montana” featured her friends, the Buckley sisters, and revealed the still-scandalous abolition of the side-saddle (an innovation, the split-skirt, that supported this change, is often attributed to Cameron herself) among Montana’s settler women. I’m almost sure her friend, Janet Williams, is wearing a split skirt (essentially a pair of extremely wide-legged pants) in the below photo, while posing with this chained coyote pup.

The Montana branch of my family eventually came further west to Washington state, where I still live. Zelma (from the gymnastics class) married Arthur when he returned from fighting in WWI. Their family soon grew to include my grandpa and his sister. During the Great Depression, they left Montana and followed an acquaintance to Washington’s Okanagan Valley to give the apple business a try. That orchard became the place where I spent a part of every summer and certain Christmases. The dramatic, beautiful landscape of the Okanagan is the standard—for me—against which all others are compared.

In the early 1900’s, a Japanese immigrant named Frank Matsura arrived—via Seattle—in this same landscape. He landed first in the frontier town of Conconully, about fifty miles south of where my family would later settle, and worked odd jobs in one of its hotels as a handyman and “roustabout.” Soon, he moved to the nearby town of Okanogan, where he became the town’s resident photographer. Matsura worked out of a storefront studio and seems to have become fast friends with everyone in the town and surrounding area: Indigenous and settler alike.

His own outsider status likely gave him a freedom to travel between groups and his images challenge the dominant narratives of “cowboys and Indians” and rough mining camps that we might imagine in this time and place. In particular, his images of Native Americans stand out among contemporary images from better known figures like Edward Curtis or Lee Morehouse. As Michael Holloman put it in a short documentary on Matsura, “[he] allowed people to be who they were in their time…he was not trying to ‘document’ Native people.”

When I saw Matsura’s work at the NW Museum of Arts and Culture last year, I returned many times to the photo above of two Okanagan women, Cecil Jim Palmanteer and Lucy Nesom. It feels subversive and complicated and refreshing. As in his self portrait with “one of his girls,” there’s a sense of comfort and play. During a time of strict gender roles and Victorian values, he provides beautiful documentation of the freedom of expression many found within the new norms and malleable boundaries of “frontier” culture.

I by no means wish to romanticize this time period, or the realities of the settler-colonial project in the American West. Immersing myself in this work has certainly challenged my own simple narratives and moral judgments of the past. It’s quite possible that my ancestors (literal and cultural) were part of a wave of violence and ethnic cleansing and part of defining a more expansive notion of “American” identity that wasn’t all bad.

The need to hold duality when we judge historical actors brings us, naturally, to Edward S. Curtis. Plenty has been written on his project of “documentation” of who he saw as “vanishing” peoples across the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. We know that his work was a project of incredible scale, taken on at great personal cost and expense. We also know that his own colonial projections of “authenticity” shaped the images he made and obscured the true nature of changing cultures and the agency of his Indigenous participants.

Not only did Curtis urge his subjects to only appear in traditional dress and provide props for them to pose with, he controlled the environment within the frame, taking care to curate a purified, idealized version of Native life that was palatable to the white imagination. In at least one case, the photo above, he went to great lengths to remove a clock from the image, erasing by hand quite effectively, only leaving behind a faint smudge between the seated men.

Were he taking the photo today, he could save time and use the “magic” editor now built in to his phone’s high-resolution camera. Maybe he could use generative fill to place something else there in the lodge between the men. A basket of corn? A bible? A pile of scalps?

As someone who spent my girlhood devouring magazines, I survived the peak of the Photoshop re-touching era that made cellulite and stretch marks disappear, waistlines tighten in post-production, and blemishes blur to non-existence. It wasn’t great, but it was categorically different than the photographic AI tools being rolled out with unchecked enthusiasm today. Without significant debate—in the name of novelty, entertainment and relentless maximization of the self—we’ve changed the nature of what a photograph is in ways that were recently unimaginable.

I don’t think mostly about the fun or self-promotional aspects of this technology. That’s certainly what advertisements for the first AI-empowered round of cell phones wants us to think about, but I think, instead, about journalism. I think about Fred Ritchin saying that he thinks the last socially impactful photos were published in 2015.

As we observe a year of genocidal dehumanization of the Palestinian people despite a barrage of real, horrific imagery, it’s worth considering the role of the photograph in the present-future.

Gaza is still on my mind, particularly as I work nearly daily with the evidence of another settler-colonialism within my heritage and the landscape I love. I hope that you are finding ways to remain awake and alive to the interconnections between us all, and to meaningfully stand in solidarity with those at the barrel-end of our flailing, fading empire. Here is some of what I’ve been/will be reading and doing along those lines, and I’ll be back with another Big Dumb Gold Rush installment (On Power) real soon.

White Awake teach-in on Palestine this Sunday 10/6 with Sumaya Awad and Rabbi Alissa Wise

JVP form to call for Arms Embargo on Israel

This excellent post from New Means: “We have to be unequivocal right now. There can be no war in the Middle East. The U.S. spent 20 years in dishonest, deadly, disastrous wars that this country should never have gotten involved with in the first place…There is, in Washington and elsewhere, a cohort that believes Arab lives are expendable, worth less than the lives of people here at home. Not only is that gross, immoral, and untrue — it also puts us all in more danger.”

This excellent post from Anam Raheem, “i saw gaza”: “Deepening my resistance has taken many forms. It looks like building a stronger relationship with spirituality. I see what’s happening in the world, I see maimed child after maimed child, and it feels so unholy. This war is for no one, it makes no one safer. It is the opposite of sacred. To resist that, I want to move closer to what is sacred.”

Finally, on Hurricane Helene and my own number one feel-good truth, that people really can and do take care of each other when shit goes down, the wonderful Margaret Killjoy writing from N.C.: “There is no overarching coordination. There is, instead, decentralized coordination. It’s working. Most people I’ve talked to have been doing specialized work for days, but they don’t know everything that is going on. No one does. People are just… talking. And coordinating. Constantly. Organically. It’s spontaneous, coordinating decentralized efforts is also a learned and practiced skill. Another friend, used to doing physical labor, is instead spending their days just biking around and introducing people to each other, figuring out who needs what. It’s working. Disaster compassion is real: we come together in crisis.”

What are you doing to stay grounded, my friends? Let’s help each other.

xoxo

trw